The southwest corner of the Walters second floor gallery is devoted to the intersection of Greek and Roman art, with a small corner room set aside specifically for Hellenistic art. We had to learn some history before we could learn about the art of this period.

Near the end of the Classical period in Greece, Alexander the Great conquered the Mediterranean world. The Roman Republic was also on the rise from about 509 BC. The Late Classical period in Greece, which started in about 400 BC, is thought to have ended with Alexander's death in 323 BC.

High Classical Greek art

Although Athens lost its dominant political and military position in the High Classical period, it was still the center of artistic and intellectual life. Philip of Macedonia (Alexander's father) hired Aristotle to be Alex's tutor, for example, and other cultures in the ancient world (Romans, Etruscans, for example) regarded Greek art and sculpture as the epitome of art. Because the late classical period in art coincides with a period of political upheaval, however, the art in the 4th Century BC no longer focused on the serene idealism of of the past, and focused more on the individual.In sculpture, Praxiteles was setting new standards for sculpture. His male figures were taller and more sensitively rendered. He also depicted the female nude, always calling her Aphrodite, of course. Praxiteles works were widely copied, and the Walters has several copies "after Praxiteles" that give us an idea of High Classical sculpture. In Satyr Pouring Wine, for example, one can see the sensitive modeling of the adolescent figure. In the complete example below, not in the Walters, one can see the more complicated body position that the sculptor was attempting to re-create. Marden noted that our Roman copies of Greek statues are often part of series, with other versions found elsewhere.

|

| Satyr Pouring Wine - Walters Art Museum |

Also after Praxiteles, the Aphrodite of Knidos shows the new fascination with the female nude. It was sensational even in its time. The Walters' copy is from 1st C. AD Rome, and is not complete; the broken right hand was intended to "modestly" cover the genital area. I wonder who broke it off?

Although not after Praxiteles, this Roman copy of Amazon shows the High Classical fascination with the female body and with elegant drapery. This statue reproduces a famous Greek original depicting an Amazon wounded beneath her right breast. It was one of several statues of Amazons entered in a sculptors' competition at the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in western Asia Minor, about 440 BC. The sculptor of this entry is believed to have been Kresilas. According to the ancient writer Pliny, the contest was judged by the sculptors themselves, and each voted for his own first and gave second place honors to a work by Polyclitus, making him the winner. Kresilas received third prize.

Grave stele in the High Classical period began to focus on personal or domestic scenes, often featuring women and children. In this example at the Walters, a young mother, who may have died from complications during childbirth, is commemorated by her family in a scene of tenderness and poignancy. She inclines her head to gaze intently at the tiny infant in her lap, whom she cradles with both hands, as her older son stands before her, holding a pet bird by its wings.

In vases, more complex patterns, and the use of white and other colors began to be a specialty of Athenian potters. In this volute krater, flowery vines, elaborately patterned drapery, extensive use of foreshortening (the technique of drawing objects from the front and creating an illusion of depth), and added color are typical of Apulian works. This vessel served as a funerary marker. On the front, the messenger-god Hermes, who also guided the dead to the underworld, waits as a woman (representing the deceased) prepares for her journey there. On the back is a warrior clothed in Campanian (southern Italy) clothing, seated in a "naiskos," or shrine.

Also in the High Classical period, goldsmithing became prominent. Marden did not stop to discuss the Ancient Treasury at all, so I will do a separate post on that subject later.

By 331 BC Alexander had occupied Egypt, Persepolis (in the Near East) and Pakistan. When he died in 323, his generals divided his domain and established separate kingdoms in Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and Persia. Trade between and among these kingdoms was common. Cultural centers were established in Antioch, Alexandria, and Pergamon, leaving Athens as just another big city. The heyday of Greece came to an end, ushering in the period known as the Hellenistic Age.

Hellenistic Art

Alexander's lasting legacy was the spread of Greek culture all over the Mediterranean world, but the worldview changed considerably. In an era of unprecedented contact among countries and peoples, there was a cosmopolitan view of the world. People began to feel that they were citizens of the world, and to be interested in other people as individuals. Artists reflected this worldview by shifting their focus from the heroic to the everyday, from gods to mortals, from serenity to emotion, from decorous drama to melodrama. They were also fiercely competitive, showing off with different poses each more complicated than the last, in a global "I can do better than that" sort of way.

Marden spent a lot of time on the floor during her discussion of Hellenistic art. She was modeling the pose of this sculpture of a drunken woman. This statue is not at the Walters, but Marden discussed it because she said was a most typical example of the genre:

Marden spent a lot of time on the floor during her discussion of Hellenistic art. She was modeling the pose of this sculpture of a drunken woman. This statue is not at the Walters, but Marden discussed it because she said was a most typical example of the genre:

There is a similar sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum in New York that Marden also mentioned:

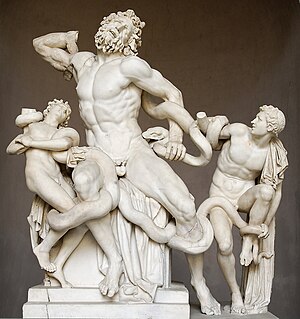

Both of these sculptures show the shift in art away from focusing on the divine and the ideal to focusing on the human, the individual, and the everyday. In both of these works you see age, ugliness and emotion, tiredness and sloppiness, melodrama. During this Hellenistic period, sculptors abandoned the strictures of Classical Greek art and experimented freely with forms and subjects. Some very famous examples from this time include Laocoön and his Sons and the Nike (Victory) of Samothrace.

|

| Laocoön and his Sons, Vatican Museum, Rome |

|

| Victory of Samothrace, Louvre, Paris |

In the Walters, there is a corner dedicated to Hellenistic art and sculpture. These crouching women playing "knucklebones" illustrate the same principles of movement, daily life, and drama that Marden discussed.

The Walters also has several statues specifically showing off the drapery, now twisting, flowing, clinging, revealing yet covering the female body in whole new ways (à la Winged Victory).

Marden did not discuss this procession of twelve deities, but it's a great piece to keep in mind for touring. Each god or goddess has distinguishing features good for discussing with kids.

By this time, Marden was talking really fast and we were just turning the corner to Rome!

Without taking the time to stop there, Marden directed us not to miss the small niche for Etruscan Art. She described the Etruscans as deeply influenced by but different from Greek art. For example, they don't care as much about the depiction of the human body. The Etruscans used motifs from the Oriental period of Greek art on jewelry and other luxury items.

|

| Pyxis and lid with Sphinx-shaped handle |

Their art also reflects the higher status of women in Etruria. Marden directed us to look at some of the cistae, cylindrical containers for women's toiletry articles, for example. Hard to see in the photo, but definitely there in the museum, one can see elaborate carved tracery lines which are thought to reflect Greek wall paintings now lost.

|

| Cista depicting a Dionysian revel and Perseus with Medusa's Head |

Okay, by now we really did turn to Ancient Roman art. Marden noted that while there was copying of Greek statues, already discussed, Roman sculptors also developed a unique approach. They started by emulating Greek art but dismissing some of its values. The Romans saw themselves as "noble, sober, simple agrarian strivers" and sought to reflect those values in their art.

We interrupt this training . . .

Marden went off on a bit of a tangent here but it was an interesting tangent so I want to remember it. While discussing the Roman copies of Greek originals, Marden noted that many of the statues at the Walters came into the collection as whole statues. Arms and heads were placed on bodies, and fragments were made into whole bodies with additions of plaster casts. It was considered appropriate to do this in the 19th Century, because many restorers and collectors thought the point was to educate the public by teaching everyone the "greatest hits." At the Walters, the "de-restoration" of statues began almost immediately, but it often took a lot of study to figure out what head went with what body, for example. For example, this Greek-looking archaic-style head was attached to this Peplos-style body but both were Roman retrospectives of Archaic Greek style and they did not belong together.

Marden reflected on the fact that there are so many moments in the life of the statue, and so many times when art historians have their hands on things.

. . . . So, What Did the Romans do besides Collect?

Marden turned first to portrait heads, of which the Walters has several. She noted that Roman Republican portraits were "veristic," that is, meant to show people as they actually looked. Often a portrait of an old man could reflect traditional republican values like wisdom, stability, practicality and determination. He also looks like he is in a bad mood - he is "concerned" about the fate of the Republic.

|

| Portrait of a republican man, circa 40 BC (late republican) |

This portrait of Marcus Aurelius reflects his contemplative nature. He was known as a "philosopher-emperor" who meditated on the ways of the gods.

|

| Marcus Aurelius |

His wife, Livia, used the same tactic, changing her fashions and her hairstyle from time to time but always appearing young and beautiful. In fact, most portraits of women were used to project idealized beauty.

Marden told us an interesting story about the complicated hairstyles worn by Roman women. For years, art historians assumed that the styles portrayed in the marble heads were really wigs. Then, recently, a Baltimore hairdresser posited that the styles were created using actual hair held together by needle and thread. Marden directed us to this article to read about this theory, now widely accepted.

|

| Livia |

Julia Domna (below) was the wife of Severus, who declared himself the son of Marcus Aurelius. He was anxious for legitimacy. Julia was the mother of 2 sons; one killed the other. I'm not sure you can read any of that in her face.

|

| Julia Domna |

Marden next turned to a discussion of Roman funerary practices. People joined funerary clubs to make sure that they would receive proper honor at their deaths. People also went to cemeteries to feast and celebrate. This framed funerary marker for a husband and wife would have been placed by the side of a road leading out of Rome as a sort of "self-advertisement." These types of markers sometimes depicted the living and the dead side by side, so we do not know who died first. Consistent with other marriage portraits, the man probably held a scroll and the woman a stylus and wax tablet. Or the woman might have held a sistrum because Roman women liked the cult of Isis. Marden noted that the sculptors of such reliefs had little regard for the rules of Classical art.

By the 1st or 2d C. Romans were favoring burial over cremation. This preference may reflect the influence of Christianity. In the 2d. C., Roman artists began to create elaborate sarcophagi. Greek mythology was one of the most popular subjects to decorate such sarcophagi. Repetitions among the sculptures indicate that the sculptors had access to pattern books. Note that in the Western Roman empire, the front and sides were decorated; in the Roman East, sarcophagi were decorated on all four sides.

The Walters has seven stunning sarcophagi. Unfortunately, by the time we reached them in our discussion, it was late in the afternoon. Either Marden didn't spend much time on the sarcophagi

or I was too tired to take notes, but I didn't catch much here. We noted the Triumph of Dionysus as one example, and Marden noted that Dionysos (Roman Bacchus) was the focus of an unofficial mystery religion popular among women. She also noted that the piling of figures so evident here represented an emphatic rejection of the Classical rules. Finally, she noted that many examples include a face of the deceased among the carvings, often as a wise man or learned intellectual. Elite Romans used their burials to advertise themselves, to tie their identities to myth, and to use myth as portraiture.

Finally, we ended in the last room devoted to the Roman house. The structure of the house was important, as the house played such an important role in Roman social rituals. There were elaborate rules about who visited whom. Houses were arranged according to rules. An entryway led to an atrium, usually with an open ceiling and a water cistern in the center. Later houses added a peristyle garden. Walls were decorated with murals, of four possible types. At the Walters, the walls behind the banquet couch are painted in the First Style to imitate costly marble panels. The Romans used painted stucco. Second Style paintings aimed to "dissolve" the walls and create the illusion of an imaginary 3D world. (The second photo below shows a room re-installed from a villa near Pompeii with excellent examples of Second Style paintings.)

|

| Roman banquet couch and wall paintings. Photo by Mary Harrsch, 2004. |

|

| Room from Villa at Boscoreale, Metropolitan Museum, New York |

We ran out of time to talk about the lararium re-created at the Walters, although Marden did note that the bronze statues in this example were all found together. John wanted to make sure that we took note of it for use on tours.

|

| Photo by Mary Harrsch, 2004 |

By this time we were fairly exhausted. Marden was an inspiration and it was a joy to listen to her, but it will take a lot of time to absorb all that she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment